Relative Clauses

NAVIGATION ADVICEThere is more information on this page than you are likely to have time for. We suggest that you proceed as follows:

|

| Summary & Exercises | Explanations & Examples | Action Mazes (Step by step practice with lots of feedback) |

| Summary | Introduction | |

| Diagnostic Exercises You will be asked 20 questions. IF YOU GET A QUESTION WRONG, KEEP TRYING UNTIL YOU GET IT RIGHT. THE PROGRAM WILL ONLY CALCULATE YOUR SCORE IF YOU HAVE ANSWERED ALL THE QUESTIONS. Incorrect guesses will reduce your score. When you are finished, click “Submit” if you are satisfied with your score. Remember you need a score of at least 80% in order to get a “check” for this assignment. | Where to position the relative clause in the sentence | |

| Where to position the verb in the relative clause | ||

| Nominative, Accusative and Dative relative pronouns | Nominative, Accusative and Dative relative pronouns | |

| Relative pronouns with prepositions | Relative pronouns with prepositions | |

| Genitive relative pronouns | Genitive relative pronouns | |

| The relative pronouns wer, wo & was | ||

| Practice Exercises | Recognizing relative clauses |

Summary and Examples

I. Introduction

- Relative clauses supply additional information about the nouns in a sentence.

- In German, the relative pronoun for people and things will be a form of der/das/die==> in particular, do not use wer (or wen or wem) to translate English who or whom:

| Da ist der Mann, der Rumpelstilzchen liebt. Da ist der Mann, wer Rumpelstilzchen liebt. |

There is the man who loves Rumpelstilzchen. |

- Relative pronouns may sometimes be omitted in English, but they cannot be omitted in German:

| Da ist der Mann, den Rumpelstilzchen liebt. Da ist der Mann Rumpelstilzchen liebt. |

There is the man (whom) Rumpelstilzchen loves. |

- The term “antecedent” is used to refer to the noun being referred to by a relative pronoun. Thus in the above example,

| Da ist der Mann, den Rumpelstilzchen liebt. | The antecedent of den is Mann. |

II. Where to position the relative clause in the sentence

- This is easy: the relative clause always comes right after the noun it is describing. Here are some examples. In each case, the relative clause is in bold print, and the noun or noun phrase it is describing is in italics. Note also that the relative clause is set off from the main clause by commas:

| Vier Studenten, die nicht sehr gesund aussehen, sitzen in der Mensa und essen. | Four students who don’t look very healthy are sitting in the cafeteria and eating. |

| Stefan trinkt viel zu viel Kaffee, der seinen Magen zerstören wird. | Stefan is drinking much too much coffee, which will destroy his stomach. |

- There is one exception to the above rule: if placing the relative clause right after “its” noun in this way would leave the verb in the main clause dangling at the end of the sentence by itself, the resulting sentence would be awkward to comprehend. In such cases, the verb is usually moved in front of the relative clause.

| Letztes Jahr haben Stefan, Silke, Anette und Torsten ein Huhn gegessen, das fünf Tage auf dem Küchentisch gelegen hatte. | Last year, Stefan, Silke, Anette and Torsten ate a chicken which had lain on the kitchen table for five days. |

| Sie werden nie die Woche vergessen, die sie danach krank im Bett verbracht haben. | They will never forget the week [which] they spent sick in bed after that. |

III. Where to position the verb in the relative clause

- This is easy also: relative clauses are subordinate clauses. Consequently, the conjugated verb comes at the end of the relative clause.

IV. Nominative, Accusative and Dative Relative Pronouns

- Nominative, Accusative and Dative relative pronouns are normally forms of der/das/die, regardless of whether they refer to a person or a thing. These differ from the forms of der/das/die which you have already learned only in the dative plural:

| Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | Plural | |

| Nominative | der | das | die | die |

| Accusative | den | das | die | die |

| Dative | dem | dem | der | denen |

- The gender of the relative pronoun is the same as the gender of its antecedent (the noun to which it is referring). The case of the relative pronoun (Nominative, Accusative, Dative or Genitive) depends on its grammatical function in the relative clause. It does not depend on the grammatical function of the antecedent in the main clause. To make this clear, here is an example of how an antecedent in the nominative case (der Laden) can be referred to by a relative pronoun in the nominative, accusative or dative case:

| Das ist der Laden, der (Nom.) die besten Gummibärchen verkauft. | That is the store that sells the best gummi-bears. |

| Das ist der Laden, den (Acc.) ich liebe. | That is the store (that) I love. |

| Das ist der Laden, dem (Dat.) ich €20.000 schulde. | That is the store to which I owe €20,000. |

- In the first case, the store is the subject of the action in the relative clause (it sells the gummi-bears), and hence is referred to by a relative pronoun in the nominative (der).

- In the second case, the store is the direct object of my love (I love it), and so is referred to by a relative pronoun in the accusative (den).

- In the third case, the store is the object of the dative verb “schulden” (to owe), and so is referred to by a relative pronoun in the dative case (dem).

V. Relative pronouns with prepositions

- In German, prepositions are inseparable from the nouns or pronouns they bring into a sentence. This applies also in relative clauses. Since they are prepositions, they will always come in front of the relative pronoun they are associated with. They will also determine the case of the relative

pronoun as follows:- Following an accusative preposition, the relative pronoun will be accusative, following a dative preposition, the relative pronoun will be dative, following a genitive preposition, the relative pronoun will be genitive.

| Ein Computer ist eine Maschine, für die man viel Geld bezahlen muß. | A computer is a machine for which one has to pay a lot of money. |

| Ein Computer ist eine Maschine, mit der man Aufsätze schreiben kann. | A computer is a machine with which one can write essays. |

-

-

- In the first case, für is an accusative preposition and is thus followed by a relative pronoun in the accusative (die).

- In the second case, mit is a dative preposition and is thus followed by a relative pronoun in the dative (der).

-

-

- Following a two-way preposition the relative pronoun will be accusative if the action in the relative clause involves motion, and dative if the relative clause is describing the location where the action is taking place.

| Ein Klassenzimmer ist ein Zimmer, in dem man Deutsch lernen kann. | A classroom is a room in which one can learn German. |

| Ein Klassenzimmer ist ein Zimmer, in das Französischstudenten nicht gern gehen. | A classroom is a room into which French students don’t like to go. |

-

-

- In the first case, the classroom is the location in which learning German can take place ==> dative

- In the second case, the relative clause is about motion into the classroom ==> accusative

- If the two-way preposition is not describing motion/location but rather is part of a verb + preposition combination (as in “sprechen über” or “warten auf”), you need to know whether that particular preposition + verb combination is associated with accusative or dative. If in doubt about this, your best guess is to choose the accusative.

-

| 1. Jeff schreibt eine Prüfung über Relativsätze, vor denen er keine Angst mehr hat. | Jeff is taking an exam about relative clauses, which he’s no longer afraid of. |

| 2. Er hat diese Webseite gelesen, an die ihn seine Lehrerin erinnert hat. | He read this webpage, which his teacher reminded him of. |

-

-

- Angst haben vor + Dative = to be afraid of

- erinnern an + Accusative = to remind (someone) of (something)

-

VI. Genitive Relative Pronouns

- The genitive relative pronouns mean “whose” and work slightly differently: once you know you are trying to say “whose,” you choose the correct genitive relative pronoun only according to the gender of its antecedent: dessen for masculine and neuter antecedents; deren for feminine and plural antecedents. The complete table of relative pronouns is thus:

| Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | Plural | |

| Nominative | der | das | die | die |

| Accusative | den | das | die | die |

| Dative | dem | dem | der | denen |

| Genitive | dessen | dessen | deren | deren |

- Some examples:

| Michael Fassbender, dessen Mutter aus Irland kommt, wurde in Heidelberg geboren. | Michael Fassbender, whose mother is Irish, was born in Heidelberg. |

| Ich bewundere Oprah Winfrey, deren Bücher ich alle lesen möchte. | I admire Oprah Winfrey, all of whose books I would like to read. |

VII. The relative pronouns wer, wo & was [221 and above]

- It sometimes happens that the antecedent of the relative pronoun is an abstract concept or place, to which one cannot assign a gender, so that it becomes impossible to chose the appropriate form of der/das/die to use as the relative pronoun. When the gender of the antecedent cannot be determined, or when there is no antecedent, wer, wo and was are used as the relative pronouns.

- Wer never has an antecedent. It is used to mean whoever, the person who, or he/she who.

| Wer auf den Mond will, muss jetzt schon einen Sitz reservieren. | Whoever wants to go to the moon already has to reserve a seat now. |

-

- Wo means where, and is used when the antecedent is a place. If the place has a proper name and no article (Berlin, Disneyland, Deutschland, Kroger), you must use wo to refer to it in a relative clause. If the place has an article (die Schweiz, die Türkei, das Klassenzimmer), you can use wo or you can use in + the appropriate form of der/das/die.

| Bergisch Gladbach, wo Heidi Klum geboren ist, ist keine sehr interessante Stadt. | Bergisch Gladbach, where Heidi Klum was born, is not a very interesting city. |

| Trotzdem kehrt sie natürlich gern in die Stadt zurück, in der sie geboren ist. Trotzdem kehrt sie natürlich gern in die Stadt zurück, wo sie geboren ist. |

Nevertheless she of course likes to return to the city in which she was born. |

-

- Was has three uses:

- Without an antecedent, it is used to mean what or whatever.

- Was has three uses:

| Was Marlene Dietrich einmalig macht, ist ihre Stimme. | What makes Marlene Dietrich unique is her voice. |

-

-

- Was is used to refer to indefinite nouns or pronouns such as alles, etwas, nichts, das Beste, das Schönste, das Neueste. In these cases, the best translation is an optional that. It will be natural for you to remember to use was in these cases, since you will not be able to decide on a gender for words such as alles, which will remind you that you cannot use der/das/die.

-

| Horst möchte alles kaufen, was Marlene Dietrich berührt hat. | Horst wants to buy everything (that) Marlene Dietrich has touched. [alles ==> was] |

| Aber: Alle Lieder, die Marlene Dietrich gesungen hat, sind wunderbar. | But: All the songs (that) Marlene Dietrich sang are wonderful. [alle Lieder ==> die] |

-

-

- Was may refer back to a whole clause, in which case it can be translated as which, or which is something (that). Again, it will be natural for you to remember to use was in these cases, since you will not be able to decide on a gender for an entire clause, which will remind you that you cannot use der/das/die.

-

| Jeden Morgen tritt Jack Nicholson meinen kleinen Hund, was mich immer wütend macht. | Every morning, Jack Nicholson kicks my little dog, which always makes me angry. [Here, the use of was means the relative clause refers to the entire previous clause, i.e. I’m mad that Jack Nicholson does this to my dog every day.] |

| Jeden Morgen tritt Jack Nicholson meinen kleinen Hund, der mich immer wütend macht. | Every morning, Jack Nicholson kicks my little dog, which always makes me angry. [Here, the use of der means the relative clause refers specifically to my little dog, i.e. the dog makes me mad all the time, which suggests that I’m probably glad that Jack Nicholson kicks it every day–a big difference!] |

-

- When a preposition is combined with wo (==>wohin, woher) or was used as described above, you must use a wo-compound.

| Diana Ross möchte wissen, ob du weisst, wohin du gehst. | Diana Ross wants to know if you know where you’re going to. |

| Es gibt nichts, wofür Diana Ross sich nicht interessiert. [für + was = wofür] | There is nothing (that) Diana Ross is not interested in. |

VIII. Recognizing relative clauses

- Work backwards from the above!

Practice Exercises

- In Hartmuts Zimmer Very basic practice to help you get used to the forms that relative clauses take. All the relative pronouns in these examples are in the Nominative (3 items–use the “weiter” button to navigate between exercises)

- Wer bin ich? Practice Nominative, Accusative and Dative Relative Pronouns by filling in the blanks with the appropriate Relative Pronouns; then guess the person being described (7 items–use the “weiter” button to navigate between exercises)

- Wer bin ich? (mit Präpositionen) Practice Relative Pronouns with (some) Prepositions by filling in the blanks with the appropriate Relative Pronouns; then guess the person being described (2 items–use the “weiter” button to navigate between exercises)

- Professor Blume Practice all aspects of relative pronouns with this exercise. All of the sentences have to do with animals and plants. Some of them are rather difficult, so don’t be discouraged if you find this unusually hard. You will get full explanatory feedback once you click on the right answer, so if you don’t succeed right away, keep trying 🙂

Practice Exercises on Other Sites

- Cumulative Practice Created by Dr. Olaf Böhlke. Fill in the correct relative pronouns in a series of statements. Includes all four cases, relative pronouns with prepositions, and indefinite relative pronouns (wer/wo/was). Click on A, B, C at the top to see all 30 items. Note the instructions for seeing feedback for each item; you may need to enter an intentionally incorrect response (e.g. das instead of der) to understand how the feedback works. Click on T/Tipp to see hints!

Explanations and Examples

I. Introduction

Relative clauses supply additional information about the nouns in a sentence.

Here are some examples of simple sentences without any relative clauses:

| Kelly spricht mit einem jungen Mann. | Kelly is talking to a young man. |

| Der junge Mann ist nervös. | The young man is nervous. |

| Er gibt Kelly sein Deutschbuch. | He gives Kelly his German textbook. |

| Im Sommer fliegen sie nach Berlin. | In the summer, they fly to Berlin. |

Here are the same sentences with relative clauses (in bold print) added to provide more information about some of the nouns, which, in this case, helps you see just how romantic the above scenario could be…:

| Kelly spricht mit einem jungen Mann, den sie sehr attraktiv findet. | Kelly is talking to a young man, whom she finds very attractive. |

| Der junge Mann, der jede Nacht von Kelly träumt, ist nervös. | The young man, who dreams of Kelly every night, is nervous. |

| Er gibt Kelly sein Deutschbuch, in dem er auf jede Seite ein Liebesgedicht an sie geschrieben hat. | He gives Kelly his German textbook, in which he has written a love poem to her on every page. |

| Im Sommer fliegen sie nach Berlin, wo sie heiraten. | In the summer, they fly to Berlin, where they marry. |

Contrastive grammar

English distinguishes between relative pronouns referring to people (who and whom) and relative pronouns referring to things or concepts (that or which). In German, the relative pronoun for people and things will be a form of der/das/die ==> do not use wer (or wen or wem) to translate English who or whom:

| Da ist der Mann, der Kelly liebt. Da ist der Mann, wer Kelly liebt. |

There is the man who loves Kelly. |

| Da ist der Mann, den Kelly liebt. Da ist der Mann, wen Kelly liebt. |

There is the man whom Kelly loves. |

Also, relative pronouns may sometimes be omitted in English, but they cannot be omitted in German:

| Da ist der Mann, den Kelly liebt. Da ist der Mann Kelly liebt. |

There is the man Kelly loves. There is the man whom Kelly loves. |

| Er trägt den Ring, den sie ihm gegeben hat. Er trägt den Ring sie ihm gegeben hat. |

He is wearing the ring she gave him. He is wearing the ring which she gave him. He is wearing the ring that she gave him. |

Terminology: “antecedent”

The term “antecedent” is used to refer to the noun being referred to by a relative pronoun. Thus in the most recent example,

| Da ist der Mann, den Kelly liebt. | The antecedent of den is Mann. |

| Er trägt den Ring, den sie ihm gegeben hat. | The antecedent of den is Ring. |

What you need to know:

- Where to position the relative clauses in the sentence (very easy!)

- Where to position the verb in the relative clause (very easy: the verb always comes at the end of the relative clause)

- How to choose the correct relative pronoun. This will be the subject of the bulk of this module, beginning with the section on Nominative, Accusative and Dative Relative Pronouns.

When you are reading or hearing German, you are also going to need to be able to go backwards, i.e. to interpret relative clauses by

- recognizing them

- identifying the antecedent of the relative pronoun (i.e. the noun which the relative clause is describing)

This will be discussed at more length at the end of this explanation, but is something students are often able to do automatically, even before having “officially” studied relative clauses.

II. Where to position the relative clauses in the sentence

This is easy: the relative clause always comes right after the noun it is describing. Here are some examples. In each case, the relative clause is in bold print, and the noun or noun phrase it is describing is in italics. Note also that the relative clause is set off from the main clause by commas:

| Vier Studenten, die nicht sehr gesund aussehen, sitzen in der Mensa und essen. | Four students who don’t look very healthy are sitting in the cafeteria and eating. |

| Stefan trinkt viel zu viel Kaffee, der seinen Magen zerstören wird. | Stefan is drinking much too much coffee, which will destroy his stomach. |

| Silke, die nie Sport treibt, isst 5 Bratwürste mit Sauerkraut, Fritten und Mayonnaise. | Silke, who never exercises, is eating 5 bratwursts with sauerkraut, fries and mayonnaise. |

| Anstatt zu essen raucht Annette Zigaretten, von denen sie hohen Blutdruck bekommt. | Instead of eating, Annette smokes cigarettes, from which she is getting high blood pressure. |

| Torsten isst ein Brot mit Butter und Nutella, das er von zu Hause mitgebracht hat. | Torsten is eating a piece of bread with butter and Nutella, which he has brought along from home. |

In the last example, note that the relative pronoun refers grammatically to the first noun (“Brot”) in the noun phrase (“ein Brot mit Butter und Nutella”) – this is why the relative pronoun is das (as in “das Brot”) and not die (as in “die Butter/die Nutella”). This will happen when the relative clause refers to a noun phrase containing more than one noun. You will most likely get such sentences right by instinct ==> please don’t let this detail worry you too much!

A minor exception: “dangling verbs”

There is one exception to the above rule: if placing the relative clause right after “its” noun in this way would leave the verb in the main clause dangling at the end of the sentence by itself, the resulting sentence would be awkward to comprehend. In such cases, the verb is usually moved in front of the relative clause.

Here are some examples of sentences that would leave a verb dangling by itself in this awkward way if the relative clause were placed right after its antecedent:

| Letztes Jahr haben Stefan, Silke, Annette und Torsten ein Huhn, das fünf Tage auf dem Küchentisch gelegen hatte, gegessen. | Last year, Stefan, Silke, Annette and Torsten ate a chicken which had lain on the kitchen table for five days. |

| Sie werden nie die Woche, die sie danach krank im Bett verbracht haben, vergessen. | They will never forget the week [which] they spent sick in bed after that. |

The verb is thus moved in front of the relative clause as follows:

| Letztes Jahr haben Stefan, Silke, Anette und Torsten ein Huhn gegessen, das fünf Tage auf dem Küchentisch gelegen hatte. | Last year, Stefan, Silke, Anette and Torsten ate a chicken which had lain on the kitchen table for five days. |

| Sie werden nie die Woche vergessen, die sie danach krank im Bett verbracht haben. | They will never forget the week [which] they spent sick in bed after that. |

III. Where to position the verb in the relative clause

This is easy also: relative clauses are subordinate clauses (eventually, you will be able to click here for more information…). Consequently, the conjugated verb comes at the end of the relative clause. Click here for some more details on this. The previous examples are printed again below, this time with the verb at the end of the relative clause in italics. Note that where the verb is in two parts, the conjugated verb comes after the “generic” one [infinitives or past participles are “generic” in the sense that they are not conjugated to agree with the subject of the action]:

| Vier Studenten, die nicht sehr gesund aussehen, sitzen in der Mensa und essen. | Four students who don’t look very healthy are sitting in the cafeteria and eating. |

| Stefan trinkt viel zu viel Kaffee, der seinen Magen zerstören wird. | Stefan is drinking much too much coffee, which will destroy his stomach. |

| Silke, die nie Sport treibt, isst 5 Bratwürste mit Sauerkraut, Fritten und Mayonnaise. | Silke, who never exercises, is eating 5 bratwursts with sauerkraut, fries and mayonnaise. |

| Anstatt zu essen raucht Annette Zigaretten, von denen sie hohen Blutdruck bekommt. | Instead of eating, Annette smokes cigarettes, from which she is getting high blood pressure. |

| Torsten isst ein Brot mit Butter und Nutella, das er von zu Hause mitgebracht hat. | Torsten is eating a piece of bread with butter and Nutella, which he has brought along from home. |

IV. Nominative, Accusative and Dative Relative Pronouns

As mentioned in the Introduction, Nominative, Accusative and Dative relative pronouns are normally forms of der/das/die, regardless of whether they refer to a person or a thing. These differ from the forms of der/das/die which you have already learned only in the dative plural:

| Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | Plural | |

| Nominative | der | das | die | die |

| Accusative | den | das | die | die |

| Dative | dem | dem | der | denen |

The gender of the relative pronoun is the same as the gender of its antecedent (the noun to which it is referring). The case of the relative pronoun (Nominative, Accusative, Dative or Genitive) depends on its grammatical function in the relative clause. It does not depend on the grammatical function of the antecedent in the main clause. To make this clear, here is an example of how an antecedent in the nominative case (der Laden) can be referred to by a relative pronoun in the nominative, accusative or dative case:

| Das ist der Laden, der (Nom.) die besten Gummibärchen verkauft. | That is the store that sells the best gummi-bears. |

| Das ist der Laden, den (Acc.) ich liebe. | That is the store (that) I love. |

| Das ist der Laden, dem (Dat.) ich €20.000 schulde. | That is the store to which I owe €20,000. |

- In the first case, the store is the subject of the action in the relative clause (it sells the gummi-bears), and hence is referred to by a relative pronoun in the nominative (der).

- In the second case, the store is the direct object of my love (I love it), and so is referred to by a relative pronoun in the accusative (den).

- In the third case, the store is the object of the dative verb “schulden” (to owe), and so is referred to by a relative pronoun in the dative case (dem).

Structured Practice (Action Mazes)

Hartmuts Zimmer This is an “action maze” designed to take you step by step through the tasks involved in choosing a relative pronoun.

Hartmuts Zimmer 2 More practice of the same sort.

V. Relative pronouns with prepositions

Click here if you need to review prepositions in general!

The preposition always precedes the relative pronoun

In German, prepositions are inseparable from the nouns or pronouns they bring into a sentence. This applies also in relative clauses. Since they are prepositions, they will always come in front of the relative pronoun they are associated with. They will also determine the case of the relative pronoun; this will be discussed below.

| Da ist Frau Müller, mit der ich jeden Tag Kaffee trinke. | There is Frau Müller, with whom I have coffee every day. |

| Sie spricht mit Herrn Schmitz, von dem ich C++ gelernt habe. | She is talking to Mr. Schmitz, from whom I learned C++. |

| Sie sitzen auf dem Tisch, an dem ich normalerweise arbeite. | They are sitting on the table, at which I normally work. |

| Sie hinterlassen immer hinternförmige Flecken auf meinem Schreibtisch, über die meine Kollegen und ich gern lachen. | They always leave behind butt-shaped stains on my desk, about which my colleagues and I like to laugh. |

In English, one needs to be reminded by one’s teacher to keep the preposition in front of the relative pronoun; in informal speaking, one is much more likely to hear the above sentences as:

|

There is Frau Müller, whom I have coffee with every day. She is talking to Mr. Schmitz, whom I learned C++ from. They are sitting on the table, which I normally work at. They always leave behind butt-shaped stains on my desk, which my colleagues and I like to laugh about. |

In German, it would be unthinkable to separate the preposition

from its relative pronoun in this way: you will never hear anyone

do this in speaking or writing.

Click here for a barely relevant and slightly rude joke on this topic.

The preposition determines the case of “its” relative pronoun

Following an accusative preposition, the relative pronoun will be accusative, following a dative preposition, the relative pronoun will be dative, following a genitive preposition, the relative pronoun will be genitive.

| Ein Computer ist eine Maschine, ohne die man diese Webseite nicht lesen könnte. | A computer is a machine without which one could not read this webpage. |

| Ein Computer ist eine Maschine, für die man viel Geld bezahlen muß. | A computer is a machine for which one has to pay a lot of money. |

| Ein Computer ist eine Maschine, mit der man Aufsätze schreiben kann. | A computer is a machine with which one can write essays. |

| Ein Computer ist eine Maschine, deren Funktionsweise ich nie verstehen werde. | A computer is a machine whose functioning I will never understand. |

- In the first two cases, ohne and für are accusative prepositions and are thus followed by a relative pronoun in the accusative (die).

- In the third case, mit is a dative preposition and is thus followed by a relative pronoun in the dative (der).

- In the fourth case, trotz is a genitive preposition and is thus followed by a relative pronoun in the genitive (deren). Genitive relative pronouns are discussed in more detail in the next section.

Following a two-way preposition the relative pronoun will be accusative if the action in the relative clause involves motion, and dative if the relative clause is describing the location where the action is taking place.

| Ein Klassenzimmer ist ein Zimmer, in dem man Deutsch lernen kann. | A classroom is a room in which one can learn German. |

| Ein Klassenzimmer ist ein Zimmer, in das Französischstudenten nicht gern gehen. | A classroom is a room into which French students don’t like to go. |

| Eine Landkarte ist ein Bild, auf dem man Deutschland sehen kann. | A map is a picture on which one can see Germany. |

| Ein Französischbuch ist ein Buch, auf das man sich setzen kann. | A French book is a book (which) one can sit down on. |

| Das Französischbuch ist das Buch, auf dem wir sitzen. | The French book is the book (which) we are sitting on. |

- In the first case, the classroom is the location in which learning German can take place ==> dative

- In the second case, the relative clause is about motion into the classroom ==> accusative

- In the third case, the map is the location where one can see Germany ==> dative

- In the fourth case, the relative clause is about the motion of sitting down on a French book ==> accusative

- In the fifth case, the French book is the location where we are seated ==> dative

If the two-way preposition is not describing motion/location but rather is part of a verb + preposition combination (as in “sprechen über” or “warten auf”), you need to know whether that particular preposition + verb combination is associated with accusative or dative. If in doubt about this, your best guess is to choose the accusative.

| 1. Jeff schreibt eine Prüfung über Relativsätze, vor denen er keine Angst mehr hat. | Jeff is taking an exam about relative clauses, which he’s no longer afraid of. |

| 2. Er hat diese Webseite gelesen, an die ihn seine Lehrerin erinnert hat. | He read this webpage, which his teacher reminded him of. |

| 3. Die Fragen, auf die er problemlos antworten kann, machen ihm Spaß. | The questions, (which) he can answer without a problem [to which he can give answers without a problem], are fun for him. |

| 4. Die Webseite hat Hartmut, auf den Jeff nach der Prüfung ein alkoholfreies Bier trinken wird, fantastisch gemacht. | Hartmut, to whom Jeff will drink a non-alcoholic beer after the test, has done a fantastic job with this webpage. |

- Angst haben vor + Dative = to be afraid of

- erinnern an + Accusative = to remind (someone) of (something)

- antworten auf + Accusative = to answer (a question) [the preposition “auf” will always refer to the question being answered; the person being answered is referred to in the dative without a preposition: Sie antwortet dem Lehrer auf die Frage]

- trinken auf + Accusative = to drink to (someone or something)

The combination “preposition + relative pronoun” may sometimes be replaced by a wo-compound. Click here for more information

Structured Practice (Action Mazes)

VI. Genitive Relative Pronouns

The genitive relative pronouns mean “whose” and work slightly differently: once you know you are trying to say “whose,” you choose the correct genitive relative pronoun only according to the gender of its antecedent: dessen for masculine and neuter antecedents; deren for feminine

and plural antecedents. The complete table of relative pronouns is thus:

| Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | Plural | |

| Nominative | der | das | die | die |

| Accusative | den | das | die | die |

| Dative | dem | dem | der | denen |

| Genitive | dessen | dessen | deren | deren |

Here are some examples:

| Michael Fassbender, dessen Mutter aus Irland kommt, wurde in Heidelberg geboren. | Michael Fassbender, whose mother is Irish, was born in Heidelberg. |

| Michael Fassbender, dessen magnetische Persönlichkeit ich gerne hätte, spielte in drei X-Men Filmen Magneto. | Barbra Streisand, whose magnetic personality I would like to have, played Magneto in three X-Men movies. |

| Ich bewundere Oprah Winfrey, deren inspirierende Interviews vielen Menschen geholfen haben. | I admire Oprah Winfrey, whose inspiring interviews have helped many people. |

| Ich bewundere Oprah Winfrey, deren Bücher ich alle lesen möchte. | I admire Oprah Winfrey, all of whose books I would like to read. |

| Ich bewundere Oprah Winfrey, durch deren Buchclub ich viele interessante Bücher entdeckt habe. | I admire Oprah Winfrey, through whose book clubs I discovered many interesting books. |

In the first two cases, the antecedent of whose is Michael Fassbender ==> use dessen, since he is masculine. It does not change anything that in the first example (dessen Mutter…), Mutter is feminine and in the second example (dessen magnetische Persönlichkeit…), Persönlichkeit is feminine: the relative pronoun will be dessen so long as the antecedent is masculine or neuter.

In the third and fourth cases, the antecedent of whose is Oprah Winfrey ==> use deren, since she is feminine. It does not change anything that in the relative clause, her interviews are the subject (they helped many people) in the third example, and her books are the object (I would like to read them all) in the fourth example: the relative pronoun will be deren so long as the antecedent is feminine or plural.

In the fifth case, the antecedent of whose is again Oprah Winfrey==> again use deren. Note that in this case, the genitive relative pronoun is preceded by an accusative preposition (durch), but this does not change the fact that you will use deren as the relative pronoun. [It does mean, however, that the noun Buchclub is in the accusative.]

==> Genitive relative pronouns are actually much simpler than the others in the sense that, once you have realized that you want to say “whose,” all you have to do to pick the correct relative pronoun is to figure out the correct gender of the antecedent, in order to choose between dessen and deren.

Structured Practice (Action Mazes)

Star Wars This is an action maze designed to take you step by step through the process of choosing a relative pronoun that may be combined with a preposition and/or that may be in the

genitive case.

VII. The relative pronouns wer, wo & was

Before reading on, you should review the information in the first section regarding the fact that the relative pronoun is normally a form of der/das/die, even if it refers to a person. This section describes the exceptions to that rule, all of which have one thing in common: it sometimes happens that the antecedent of the relative pronoun is an abstract concept or place, to which one cannot assign a gender, so that it becomes impossible to chose the appropriate form of der/das/die to use as the relative pronoun. When the gender of the antecedent cannot be determined,

or when there is no antecedent, wer, wo and was are used as the relative pronouns.

Wer

Wer never has an antecedent. It is used to mean whoever, the person who, or he/she who in sentences such as:

| Wer auf den Mond will, muss jetzt schon einen Sitz reservieren. | Whoever wants to go to the moon already has to reserve a seat now. |

| Ich weiß nicht, mit wem ich auf den Mond fliegen möchte. | I don’t know who I would like to fly to the moon with. |

Note that in each case, there is no antecedent for wer.

Wo

Wo means where, and is used when the antecedent is a place. If the place has a proper name and no article (Berlin, Disneyland, Deutschland, Kroger), you must use wo to refer to it in a relative clause. If the place has an article (die Schweiz, die Türkei, das Klassenzimmer), you can use wo or you can use in + the appropriate form of der/das/die:

| Bergisch Gladbach, wo Heidi Klum geboren ist, ist keine sehr interessante Stadt. | Bergisch Gladbach, where Heidi Klum was born, is not a very interesting city. |

| Trotzdem kehrt sie natürlich gern in die Stadt zurück, in der sie geboren ist. Trotzdem kehrt sie natürlich gern in die Stadt zurück, wo sie geboren ist. | Nevertheless she of course likes to return to the city where/in which she was born. |

Click here for information on some other uses of wo in colloquial speech, especially in Southern Germany, Austria and Switzerland.

Was

Was has three uses:

(i) Without an antecedent, it is used to mean what or whatever.

| Was Marlene Dietrich einmalig macht, ist ihre Stimme. | What makes Marlene Dietrich unique is her voice. |

| Was ich nicht weiß, macht mich nicht heiß. | What I don’t know won’t bother me. |

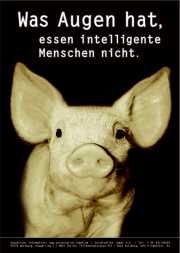

|

What has eyes, intelligent people don’t eat. [i.e. Intelligent people won’t eat anything that has eyes] |

(ii) Was is used to refer to indefinite nouns or pronouns such as alles, etwas, nichts, das Beste, das Schönste, das Neueste. In these cases, the best translation is an optional that. It will be natural for you to remember to use was in these cases, since you will not be able to decide on a gender for words such as alles, which will remind you that you cannot use der/das/die.

| Horst möchte alles kaufen, was Marlene Dietrich berührt hat. | Horst wants to buy everything (that) Marlene Dietrich has touched. [alles ==> was] |

| Aber: Alle Lieder, die Marlene Dietrich gesungen hat, sind wunderbar. | But: All the songs (that) Marlene Dietrich sang are wonderful. [alle Lieder ==> die] |

| Das Beste, was man tun kann, ist sein Leben Marlene Dietrich zu widmen. | The best thing (that) one can do is to dedicate one’s life to Marlene Dietrich. [das Beste ==> was] |

| Aber: Das beste Lied, das Marlene Dietrich gesungen hat, ist “Ich bin von Kopf bis Fuß auf Liebe eingestellt.” | But: The best song (that) Marlene Dietrich sang was “Ich bin von Kopf bis Fuß auf Liebe eingestellt.” [das beste Lied ==> das] |

| Nichts, was die Nazis ihr angeboten haben, konnte Marlene Dietrich dazu bringen, einen Film in Nazi-Deutschland zu drehen. | Nothing (that) the Nazis offered her could bring Marlene Dietrich to make a movie in Nazi Germany. [nichts ==> was] |

(iii) Finally, was may refer back to a whole clause, in which case it can be translated as which, or which is something (that). Again, it will be natural for you to remember to use was in these cases, since you will not be able to decide on a gender for an entire clause, which will remind you that you cannot use der/das/die.

| Wenige Leute in Amerika kennen Marlene Dietrich, was ich nicht verstehen kann. | Few people in America know Marlene Dietrich, which is something I cannot understand. |

| Sie werden keinen Genus für einen ganzen Satz wählen können, was Sie daran erinnern wird, “was” zu benutzen. | You will not be able to choose a gender for an entire clause, which will remind you to use “was.” |

| Jeden Morgen tritt Jack Nicholson meinen kleinen Hund, was mich immer wütend macht. | Every morning, Jack Nicholson kicks my little dog, which always makes me angry. [Here, the use of was means the relative clause refers to the entire previous clause, i.e. I’m mad that Jack Nicholson does this to my dog every day.] |

| Jeden Morgen tritt Jack Nicholson meinen kleinen Hund, der mich immer wütend macht. | Every morning, Jack Nicholson kicks my little dog, which always makes me angry. [Here, the use of der means the relative clause refers specifically to my little dog, i.e. the dog makes me mad all the time, which suggests that I may be glad that Jack Nicholson kicks it every day–a big difference!] |

Wo-Compounds

Wo-compounds must be used when a preposition is combined with wo (==>wohin, woher) or was used as described above.

| Diana Ross möchte wissen, ob du weisst, wohin du gehst. | Diana Ross wants to know if you know where you’re going to. |

| Es gibt nichts, wofür Diana Ross sich nicht interessiert. [für + was = wofür] | There is nothing (that) Diana Ross is not interested in. |

| Ich gehe nach Prag, woher der Schriftsteller Franz Kafka, der Dichter Rainer Maria Rilke, der Schriftsteller und Politiker Vaclav Havel, und Madeleine Albright kommen. | I’m going to Prague, where the author Franz Kafka, the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, the author and politician Vaclav Havel, and Madeleine Albright also come from. |

| Dort werde ich Kafkas Geburtshaus sehen, worauf ich mich sehr freue. [auf + was = worauf] | There, I will see the house in which Kafka was born, which I’m really looking forward to. [By using worauf, i.e. auf + was, the relative clause refers to the entire previous clause: what I’m looking forward to is seeing the house Kafka was born in.] |

| Dort werde ich Kafkas Geburtshaus sehen, auf das ich mich sehr freue. | There, I will see the house in which Kafka was born, which I’m really looking forward to. [By using auf das, the relative clause refers specifically to Kafka’s birth house: what I’m looking forward to is the house Kafka was born in.] |

| Danach werde ich hoffentlich vieles, worüber Kafka in seinem Tagebuch geschrieben hat, besser verstehen. [über + was = worüber; was refers to vieles] | After that I will hopefully understand better many of the things (which) Kafka wrote about in his diary. |

Wo-compounds may also be substituted for preposition + der/das/die when the antecedent is not human, but this is almost always optional. We will want you to be able to understand this when you see it, but will not expect you to do it yourself unless you want to. Click here for more information.

Recognizing relative clauses

To do this, just work backwards from your knowledge of relative clauses. Knowing that a clause is a relative clause is very helpful in understanding a sentence in two ways:

- You will know that the relative clause (normally) describes the noun just preceding it.

- You can first ignore the relative clause and figure out what the main clause means, and then go back and figure out what the relative clause is telling you about the noun just preceding it.

Here are the keys to recognizing relative clauses:

- Relative clauses follow the noun they are describing, and are set off from the main clause by commas.

- As you will have seen in the examples above, relative clauses are often at the end of a sentence, but they can also just as well come right in the middle of a main clause. The relative clause provides information about the noun it refers to, and then the main clause continues.

- A relative clause contains at least a subject and a verb (which will always be at the end of the clause). This distinguishes it from an apposition, which does not contain a verb. The distinction is not crucial for comprehension purposes, as both relative clauses and appositions serve

the same basic purpose of describing the noun just preceding them, but here are some examples:

| Steffi Graf, die eine fantastische Tennisspielerin war, ist jetzt Andre Agassis Frau. [die eine fantastische Tennisspielerin war contains a verb (war) and is a relative clause] | Steffi Graf, who was a fantastic tennis player, is now Andre Agassi’s wife. |

| Steffi Graf, die fantastische Tennisspielerin, ist jetzt Andre Agassis Frau. [die fantastische Tennisspielerin does not contain a verb and is an apposition] | Steffi Graf, the fantastic tennis player, is now Andre Agassi’s wife. |

| Boris Becker, der viele Tennisturniere gewonnen hat, spielt auch kein Profitennis mehr. [der viele Tennisturniere gewonnen hat contains a verb (gewonnen hat) and is a relative clause] | Boris Becker, who has won many tennis tournaments, also no longer plays pro tennis. |

| Boris Becker, der erfolgreiche Tennisspieler, spielt auch kein Profitennis mehr. [der erfolgreiche Tennisspieler does not contain a verb and is an apposition] | Boris Becker, the successful tennis player, also no longer plays pro tennis. |

- A clause beginning with a form of der/das/die not immediately followed by a noun [or with a preposition + a form of der/das/die not immediately followed by a noun], and ending with a verb, must be a relative clause.

Things work slightly differently if a relative clause begins with wer, wo, was, or a wo-compound, since then the relative clause often is not referring to a noun just preceding it. In order to interpret such clauses, you should refer to the explanation above of the relative pronouns wer, wo & was.